Interview with Manchala Deenabandhu on the subject of casteism

|

Interview with Manchala Deenabandhu on the subject of casteism

|

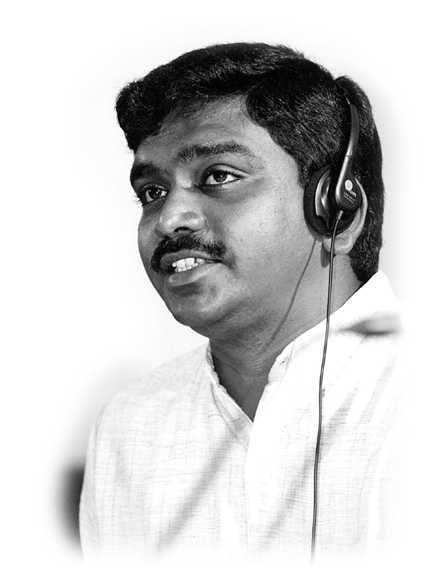

Rev. Manchala Deenabandhu - Photo: Chris Black, WCC |

ECHOES: One does not hear the word "racism" in India. Of course you hear of casteism. Tell me about it. Deenabandhu: There is racism in India although not the way it is experienced elsewhere in the world. Casteism is the synonym for racism in India. Caste is a system of hierarchy by which people are put into rigid social categories. These categories are not based on physical features but on the religious ideology of Brahminical Hinduism (Hindutva) which holds that people are born with certain qualities (varnas) and therefore some are born superior and others inferior. Thus it advocates that one’s social status is determined by birth and that one cannot simply get out of it. Caste, therefore, is a culture that ensures powers and privileges to the dominant through the subjugation and exploitation of the lower castes. This pervasive culture has a decisive hold on Indian social behaviour and relationships. Community is always conceived as caste community, resulting in social distance and the discrimination and subjugation of the lower castes in all spheres of life. The prevalence of the practice of untouchability even today in the Indian villages, despite several laws restricting it, makes casteism more dehumanising than racism. The Dalits (Untouchables) live outside the village, are not allowed entry into temples, are served food and beverages in separate cups at teashops, and even have separate burial grounds. They are told that they are not only inferior but des-picable and untouchable. This is the most inhuman expression of the Indian society’s racism, called casteism. E: We talk about racism being a combination power and privilege. Does that apply to casteism? D: Absolutely. Because of this deep-rooted religio-cultural legitimisation, the dominant caste communities have monopolised power, privileges and assets to themselves, and are able to ensure loyalty and obedience from the lower castes. Even today, a large number of the victims of caste system believe that it is divinely ordained that they should thus live and be treated. The practice of caste by its victims has been its strength. E: Would you say that racism and casteism are the same? D: Yes. These two cultures of domination and exclusion penalise people for no fault of their own and deny them a dignified human identity. But there are some differences. As I said earlier, caste is based on a religio-cultural ideology, and that makes the task of combatting caste and dealing with caste discrimination very difficult. Secondly, in situations where racism is practised, you are able to identify the victim straight away. By making certain political decisions, you can also ensure relative justice to the victims. But caste has a different operating principle. The Indian government swears by an egalitarian constitution that prohibits any form of discrimination in public life. But the fact is that it is everywhere. Caste loyalties play a decisive role in all social, political and economic formations, decisions and dynamics. |

Kusumpur is one of the many slums which surround Delhi. 40’000 people live here most of them Dalits and Indigenous. - Photo: Peter Williams, WCC. |

E: Racism can be described as the assumptions people make about other people that they put into practice because they have the power to do so. They act on those assumptions, using their power to discriminate. It seems to me that in casteism there are no assumptions but definite demarcations. D: There are assumptions. But these are used as instruments of exclusion to justify and perpetuate the hegemony of those who have managed to grab positions of power and privilege. The upper castes’ behaviour is glorified and the lower castes’ limitations are derided. One’s social behaviour, skills, abilities, etc. are seen along caste lines. These assumptions have dehumanised and continue to dehumanise the Dalits. They suffer multiple forms of disabilities, and the prominent among these is the assumption that their touch is polluting, that they are not capable of learning, not worthy enough to think and decide, but are made only for hard physical labour and for the service of others. Even if many of them do not do any polluting jobs any longer, their polluted identity remains. Is this not a form of racism? E: Racism exists in other parts of Asia. In India it is casteism. It is said that racism is like a poison in a society, and that no society can live with that poison. Is that true for casteism? D: Yes. But Indian society has lived with this poison for nearly 3500 years and continues to do so. However, I hasten to assert that it has been a poison for millions of people who have been its victims, who have been denied the right to live as human beings. Furthermore, since caste has such a pervasive hold on every sphere of life including our political life, it has virtually prevented the emergence of any just, progressive and inclusive ideological rallying points to help us march into the future as one strong nation. Caste has become a tool of grabbing and wielding power. Each caste group tries to assert its prominence and hegemony over the rest. Some fields of public life are monopolised by certain caste communities. It is certainly a kind of poison that divides people, destroys creativity and makes people insensitive to the dehumanisation it causes. |

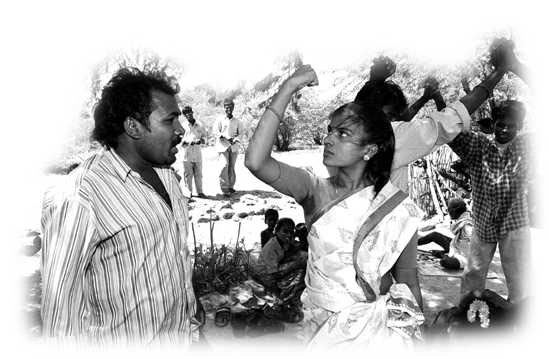

Community educators present the suffering of the Dalits through a drama in Kanglvakam, a Dalit village about 45 km south of Chennai/Madras. - Photo: Peter Williams, WCC.

|

E: What does it mean to be a Dalit in the current political situation in India, with the rise of Hindutva and Hindu nationalism? D: Firstly, as I said earlier, the current political situation is marked by the fragmentation of political power. Narrow ideologies, local issues and local parties dominate the national political scene. These narrow political interests lack ideological bases capable of guiding the life and future course of a nation as large and diverse as India. These local powers exploit caste, ethnic, religious, linguistic, and other, sentiments to consolidate their hold over the masses. The Dalits gain nothing from these powers except unfulfilled promises and continued bondage. Secondly, the protagonists of Hindutva are the wealthy upper castes who have monopolised the country’s business and industry and, using the pretext of India’s economic growth, are striving hard to see that their interests are met in the market world. This version of cultural nationalism, as preached and practised by those who have benefitted from the caste system, can only be destructive to the majority of Indians - nearly four-fifths of the population. And the Dalits are its worst victims. Thirdly, during the past two decades there has been a significant trend of growing awareness and solidarity among the marginalised sections of the Indian society. The rural and urban poor - who are mostly the Dalits, tribals, backward castes, women, agricultural labourers - are getting organised and are threatening to shake the unjust foundations on which Indian society stands. Hindutva forces want to deal with this growing solidarity among the oppressed by sowing seeds of hatred along communal lines, and thus ensure their continued hold over the politics and economy of the country. The recent atrocities against Christians in Gujarat and Orissa illustrate this point. These hitherto oppressed and exploited tribal communities, with the moral strength and dignity their new faith has given them, began to raise their voices against unjust wages and unfair treatment. So right-wing political leaders want a debate on conversions, not on the evil practice of caste. They hope thereby to arouse Hindu sentiments and cover up some of the gross injustices. E: Do you think the caste system will be overthrown? D: As a Dalit and as a part of the Dalit movement, I am committed to the vision of a casteless Indian society. But it has always been and is a very arduous struggle. Caste is changing its manifestations and dynamics. Today it has become a political weapon. Caste identities are an important feature in the political games. Political adjustments, alignments and compromises take place along caste lines. Within this ethos, the Dalits are also getting organised politically, but without a well-marked ideological focus. Unfortunately, instead of fighting caste by submerging their given caste identities, some Dalits have begun to fight with each other in some places. So, it seems to me that caste will be with us for some time. The silver lining is that Dalits and Bahujans (backward castes) are struggling hard to overcome these internal divisions and to fight together to overthrow the shameful practice of caste. These movements of the despised are the only hope for a united and progressive India. What is needed is a coordinated effort to develop a strong and pragmatic Dalit ideology that would inspire the victims of caste to shed their given identities and to work together for a society free of discrimination and oppression. Manchala Deenabandhu is presently working in the Justice, Peace and Creation team of the WCC as executive secretary for Peace concerns. He comes from Andhra Pradesh, India, and is a member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in India. In 1994 he became assistant professor in the Department of Dalit Theology in Gurukul, Madras. He has written several books and published many articles and papers. |