|

|

1999: The Year in Review

After Harare |

The year following an assembly of the World Council of Churches is mainly a time of planning. The assembly, at which every WCC member church is represented directly, is mandated to set broad policy guidelines for the next seven years. Typically, however, its size and diversity, the sense of enthusiasm it generates and its short duration result in an array of heightened expectations, new ideas and urgent recommendations far in excess of the resources available. Turning this into a realistic and effective agenda for seven years thus requires considerable reflection, consultation and focusing.

In this respect, 1999, beginning less than three weeks after the adjournment of the eighth assembly in Harare, Zimbabwe, was like all post-assembly years. The Programme Guidelines Committee report in Harare acknowledged candidly that it had not finished the task of fitting its recommendations for future WCC activities into the overall policy framework it had proposed. But four factors gave the planning undertaken in 1999 a special degree of intensity.

1. The Harare assembly said the policy statement "Towards a Common Understanding and Vision of the WCC" (CUV), adopted by the Central Committee in 1997, should be the "framework and point of reference" for developing and evaluating future WCC programmes. But behind the CUV text - and the process of study and consultation out of which it emerged - lay the recognition, reiterated by the Programme Guidelines Committee, that the WCC can no longer do "ecumenical business as usual". Central to the new understanding and vision is the WCC’s identity as a "fellowship of churches". Strengthening and deepening this fellowship is "both a task and a way of carrying out the work", as the Central Committee said at its meeting in September. Thus the WCC’s methods of work and allocation of resources should reflect this vision.

2. A new internal WCC structure, designed to correspond to the insights of the CUV process, came into being on 1 January 1999. Thus the post-Harare planning process was undertaken by a staff newly configured into four clusters and 15 teams and mandated to give much greater emphasis than previously to the integration of work across the entire Council. This entailed a planning process that was much more deliberate, consultative and time-consuming than most staff were accustomed to.

3. Throughout the year, projections of future financial resources did not encourage visions of vastly expanded WCC programmes. The announcement in October that the Board of Global Ministries of the United Methodist Church would give US$1.5 million to endow a chair in mission at the WCC’s Ecumenical Institute in Bossey was a welcome exception. In the end, the preliminary financial report for 1999 showed an unexpected surplus, but this was due to unusually good results from the Council’s investments. Although intensified contact with funding partners helped to ensure continued support, income from traditional donors continued to decline; and projections for 2000 - when most of the activities being planned in 1999 would be inaugurated - suggested that this trend would not quickly be reversed. (A complete audited financial report for 1999 will be published later in the year.)

4. A notable consequence of several years of declining income has been a steady decrease in the number of WCC staff. With fewer human resources, less work can be taken on. But it is not easy to reduce the expectations of either the member churches or the staff. The CUV discussions had recognized the importance - for not only economic but also ecumenical reasons - to increase the WCC’s collaborative work with other partners. There has been much talk of "outsourcing", "decentralizing", "joint ventures" and the like. But procedures for this take time to set up and, if anything, this makes the planning stage more rather than less complicated.

Focusing the plans

The focal point for the planning process was the meeting in Geneva of the Central Committee at the end of August and beginning of September. Apart from a brief organizational session in Harare, this was the first gathering of the 150-member body which will guide the Council’s work until 2005.

The great majority of members of this Central Committee have not previously served in this capacity. Moreover, the new WCC Rules, revised in the light of the CUV discussion, emphasize the deliberative role of the Central Committee, assigning more detailed management oversight to the Executive Committee. The organization of this first meeting sought to take account of these factors. During several sessions, the Committee met in small groups, creating a space in which more participants had a chance to speak than is possible in the rather formal parliamentary context of typical plenary sessions.

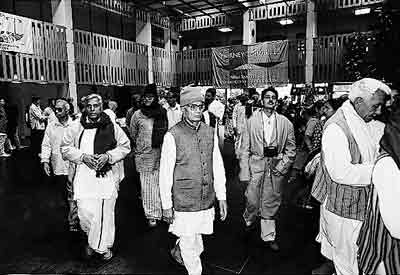

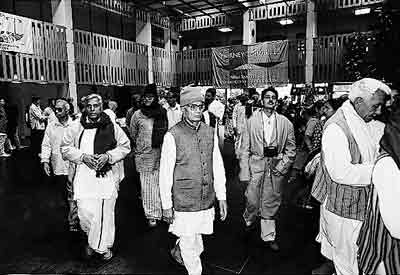

A plenary session during the 1999 meeting of the WCC Central Committee at the Ecumenical Centre in Geneva. |

|

To encourage members to see the Central Committee as a place for sharing and listening to the concerns and priorities of the member churches, a series of "Padare" offerings was arranged early in the meeting. This smaller-scale version of a model first used at the Harare assembly made it possible to discuss a range of current concerns - from ecumenical hermeneutics to the World Trade Organization, from evangelism to the Kosovo crisis, from the future of Europe to the future of religion - without limiting the discussion to WCC programmes or obliging Committee members to formulate recommendations and take decisions.

A key role in the meeting was played by the Programme Committee. This 40-member permanent sub-committee of the Central Committee was created as a means of promoting the integration and theological coherence of all the activities of the WCC. Within the Central Committee structure, it replaces the former division into several unit committees, each overseeing specific areas of work.

Drawing on preparations by staff, the Executive Committee and an ad hoc meeting of some of its own members in June, the Programme Committee looked at both a framework for the seven-year period until the next assembly and criteria for setting priorities among the emerging plans for activities over the next three years. |

Future meetings of the Programme Committee will also have reports and recommendations from the advisory bodies named by the Central Committee - four commissions, one Board and seven advisory groups - to work with; but for the 1999 meeting reports were only available from the advisory bodies for Faith and Order and Bossey.

The Programme Committee recommended and the Central Committee agreed that four themes should set the overall framework for the Council’s work: being church, caring for life, the ministry of reconciliation, and common witness and service amidst globalization. Within this framework, "staff teams would need to coordinate their work across programmatic lines".

These four general themes sketch a profile of the WCC in broad strokes; and not much attention could be given to the particular activities that will fill in the details; these were to emerge from the further process of planning following the meeting of the Central Committee. The few specifics in the Programme Committee report largely relate to proposals from the assembly and to WCC activities already underway before Harare. Thus "being church" is related to the quest for inclusive community among churches divided by racial or ethnic antagonism, the subject of an ongoing Faith and Order study; "caring for life" recalls, among other things, the assembly’s focus on Africa; globalization is recognized again as not only a matter of economic and political power structures but also a challenge to our ideas of mission, proselytism and religious freedom in a world of many faiths.

Regarding this latter point, a number of small consultations involving the team on Inter-Religious Relations and Dialogue in 1999 contributed to the ongoing reflection within the WCC. In April there was an interfaith (Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Christian) and interdisciplinary (social scientists, biblical scholars, theologians, liturgists, artists) workshop at Bossey which asked "What difference does religious plurality make?" Forty Christians and Muslims met in Hartford, Connecticut, in October to continue a discussion on "religion, law and society" initiated by the WCC some years ago. It is hoped that this may eventually lead to creation of a permanent Christian-Muslim forum on human rights. And the dialogue between Iranian Muslims and representatives of the WCC, begun in 1996, continued with a third meeting in Geneva in December on the "future of religion".

The economic and political dimensions of globalization were by no means ignored. At a press conference shortly before the June summit meeting of the G-8 countries in Cologne, the WCC released a statement strongly criticizing their proposals for alleviating the debt crisis and calling for a more radical approach that would combine initiatives for debt cancellation with reform of the international financial and trading systems, giving governments and civil society more control of the transnational flow of capital.

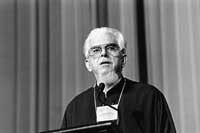

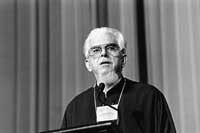

Globalization was the focus of several WCC events in June. Above, economist Susan George; right, visiting Indian farmers. |

|

|

At a public round table after the press conference Susan George, associate director of the Transnational Institute, spoke of the growing impact of the World Trade Organization on employment, consumers, the environment, development, human rights and democracy. Earlier that day, the WCC had received a delegation of more than a hundred farmers who had come to Geneva from India to protest the influence of WTO. Describing the delegation as a contribution to "globalization from the grassroots", WCC general secretary Konrad Raiser noted that "it is not enough merely to confront the major actors [in globalization], but we need in addition to search for just and sustainable alternatives".

On one of the four themes identified by the Central Committee - the "ministry of reconciliation" - more detailed programmatic discussion took place. The focus was a major long-term initiative decided by the Harare assembly: the proclamation of a Decade to Overcome Violence (2001-2010). The Central Committee approved the basic approaches for the Decade and set out five goals:

- addressing the whole spectrum of violence, in all its varieties;

- challenging the churches to affirm reconciliation and to renounce the "spirit, logic and practice" of violence;

- understanding security in terms of cooperation and community rather than domination and competition;

- working with communities of other faiths against the misuse of religious and ethnic identities in pluralistic societies;

- challenging the growing militarization of the world, especially the proliferation of small arms and light weapons.

Fundamental to the overall approach is the recognition of positive work already being done by churches and local community groups in violent contexts. The WCC has the role of facilitating exchanges among these groups and highlighting their experiences of building and keeping peace. Thus the Decade, rather than being a monolithic programme centred in Geneva, will offer a variety of entry-points and use a variety of approaches, including studies, campaigns, education, worship and spirituality, and collecting and sharing stories, using a full range of media, especially the World Wide Web.

The Decade itself, to be launched through simultaneous events at a number of places around the world in January 2001, will build on what the Central Committee described as "the WCC’s rich heritage" of engagement in issues of peace and justice.

Several WCC actions during 1999 extended this ecumenical tradition and foreshadowed some of the difficult and critical concerns on the Decade agenda. One was an Easter appeal for peace issued by the WCC’s general secretary with six other international ecumenical leaders. It pleaded for a "cessation of armed conflicts", noting that many hidden wars in other parts of the world were taking an even more terrible toll in human suffering than the conflict then raging in the Balkans. "As we remember again the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, the one proclaimed by the prophets as the Messiah, the Prince of Peace, our hearts are heavy," the appeal said, "for we recognize that we have not yet been able to overcome an inclination to turn to the sword in moments of doubt and fear."

Another WCC statement endorsed an appeal from churches in the NATO countries urging the alliance, then celebrating its 50th anniversary, to take action to eliminate nuclear weapons and, as steps towards this goal, to reduce the alert status of its member states’ nuclear weapons and renounce the first use of nuclear weapons. The WCC addressed a similar appeal to the other states which have nuclear weapons.

The WCC was one of the founding members of the International Network on Small Arms, established at a meeting in The Hague in May. Its membership of more than 200 non-governmental organizations makes it one of the largest international NGO campaign networks since the anti-landmines campaign.

Building a fellowship

While building the WCC as a "fellowship of churches" cannot be separated from engaging churches in the Council’s "programmatic" activities, the Harare assembly did acknowledge the urgency of giving focused attention to the "relational" dimension of the WCC as well. Of particular concern were increasingly vocal objections from Orthodox churches to certain developments within the WCC’s Protestant member churches, some activities of the Council itself and an overall lack of progress in ecumenical theological discussions. Strengthening their discontent was the conviction that the very structure of the WCC works against meaningful Orthodox participation.

In response, the assembly mandated the formation of a Special Commission on Orthodox Participation in the WCC. Its work is expected to last three years, leading to the eventual preparation of proposals for "necessary changes in structure, style and ethos of the Council". Half of its 60 members are appointed by Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches, half are appointed by the Central Committee to represent the WCC’s other member churches. Under the co-moderatorship of Metropolitan Chrysostomos of Ephesus (Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople) and Bishop Rolf Koppe (Evangelical Church in Germany), the Commission held its first meeting in Morges, Switzerland, in December.

|

|

Co-moderators of the Special Commission on Orthodox Participation in the WCC, Rolf Koppe (left) and Chrysostomos of Ephesus. |

|

|

Four sub-committees were named to meet during 2000 around four central issues and to report back to its next plenary session in October: (1) the organization of the WCC; (2) the style and ethos of the Council; (3) theological convergences and differences between Orthodox and other traditions in the WCC; and (4) existing models and new proposals for a structural framework that would enable meaningful Orthodox participation in the Council.

Discussions at this first meeting, which focused on the Commission’s mandate and working procedures, were constructive and cordial. In a closing communiqué, participants reiterated the hope voiced by the Harare assembly "to grow together" and to "continue the journey ‘towards a common understanding and vision’".

A regular means of strengthening bonds within the WCC is through visits: hosting delegations from member churches at the Ecumenical Centre in Geneva or sending teams to churches and ecumenical partners in various countries.

Among those coming to Geneva for official visits during 1999 were the leaders of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland, the French Protestant Federation and the Evangelical Church in Germany. There were also teams from the Church of Norway and the Church of Sweden, organized by their ecumenical officers. Throughout the year, numerous members of member churches passed through the WCC’s central offices, some in connection with programmatic work, many others as part of groups for whom an introduction to the WCC’s work was arranged.

A WCC delegation headed by general secretary Konrad Raiser visiting the Democratic Republic of Korea in April. |

|

General secretary Konrad Raiser made several official visits to member churches in 1999. His April trip to northeast Asia included the first visit by a WCC general secretary to North Korea. Besides strengthening relations with the Korean Christian Federation, the institutional expression of Protestant Christianity in North Korea, the trip was intended to highlight the WCC’s readiness to render humanitarian assistance to the country by presenting a shipment of relief supplies on behalf of Action by Churches Together (ACT) worth more than US$4 million, and to reaffirm to government representatives the WCC’s commitment to reconciliation and peaceful reunification of the Korean peninsula. |

Later, in South Korea, Raiser had an extended conversation with President Kim Dae Jung. He also met with the leaders of the three WCC member churches in the country (two Presbyterian and one Methodist) and the primates of the Anglican Church (which was received into WCC membership later in the year) and the Roman Catholic Church.

The general secretary’s trip to four regional churches in the eastern part of Germany in May renewed WCC contacts with a sector of German Protestantism which was very active ecumenically in the years before the fall of the Berlin wall, particularly in the WCC’s Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation (JPIC) process, and which is now facing new challenges to mission, service and ecumenism while struggling with structural problems and severe financial limitations. During the latter years of the German Democratic Republic, the international ecumenical links of the East German church legitimated its efforts to open spaces for critical public discussion, ultimately giving it a central role in the dramatic changes of 1989. Ten years on, it is seeking new ways of "being church" and witnessing in a context where the rates of church affiliation are among the lowest in Europe.

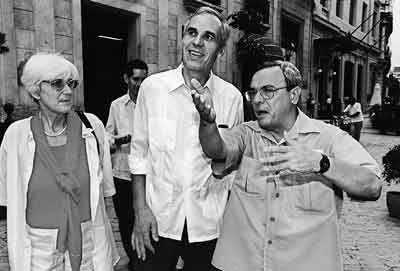

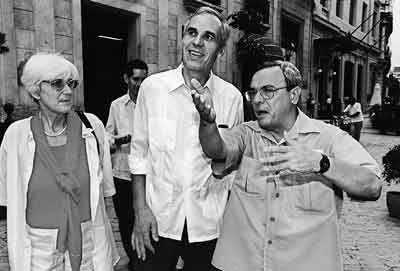

| An October visit to Cuba brought an ecumenical delegation headed by the general secretary into contact with some other member churches facing new challenges to their ministry and witness in a changing situation - in this case, a religious revival reflected in growing congregations and, most dramatically, in a public celebration which had attracted some 200,000 people to Havana’s Revolution Square in June, among them President Fidel Castro. Besides its visits with leaders of the Cuban Council of Churches, the faculty of the ecumenical seminary in Matanzas and the Roman Catholic archbishop, the group had a dinner with Castro which led into a late-night discussion on a wide range of theological, spiritual and historical topics.

Following the visit to Cuba, the WCC team travelled to Costa Rica and Honduras for encounters with churches, ecumenical bodies and relief organizations, particularly those occupied with rehabilitation one year after the devastation wrought by Hurricane Mitch in 1998. |

|

During the visit of the official WCC delegation to Cuba in October, a tour of Havana’s historic old city. |

A highlight of Raiser’s November visit to WCC member churches and theological faculties in the Czech Republic was a meeting with ten persons who had been part of a dissident network within the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren during the period of communist rule. The general secretary had asked that such an encounter be included in his visit to the country in the hope of opening up a critical and perhaps painful dialogue about the WCC’s stance during the cold war.

In the conversation, the Czech dissidents raised three principal concerns: (1) that the WCC’s efforts during the cold war to hold together the churches of East and West in a kind of "co-existence" did not allow space for a genuine dialogue that would have included all the divergent positions within the churches; (2) that the Council’s concentration on issues of justice in the third world during the 1970s and 1980s diminished its capacity to analyze and assess the human rights situation in Central and Eastern Europe; (3) that the WCC’s focus on relations with official church institutions in effect allowed the communist governments to be "censors" of all ecumenical relationships, so that information and appeals from other parts of the church - if they reached the WCC at all - were not taken seriously.

The general secretary acknowledged in response that the Council had not recognized the depth of the movement behind such "dissident" initiatives within the Czech Republic. What efforts it had made to support the dissidents were too limited and hidden to make much difference. However, he also pointed out that dialogue on this matter is often hampered by one-sided and distorted interpretations of what actually happened at particular moments, and that some of the disagreements about what the WCC ought to have done reflect basic differences in assessment and ethical judgment of the situation. What is most important now, said Raiser, is for all voices to be heard and for this often painful history to be revisited together.

There were several other impulses for taking a new look at the effects of the cold war on the ecumenical movement. In an interview with Ecumenical News International after attending a May consultation at the Protestant academy in Mühlheim, Germany, Raiser suggested that during the 1980s the WCC and other international ecumenical organizations had not taken seriously enough the impulses for change building up in Eastern and Central Europe. There was some justification for the claim by dissident groups in the formerly socialist countries of Europe that they had been "marginalized" by the WCC in comparison with the Council’s open support for ecumenical action groups struggling - sometimes in conflict with the position of the WCC’s own member churches - against oppressive governments in Latin America, South Africa and some parts of Asia.

Raiser told ENI that the WCC had been strongly influenced by the policy of détente in the late 1960s and 1970s, which sought to promote better relations with Eastern Europe and to "break out of the rigidities of the cold-war confrontation". The Council tried "to maintain that delicate space where dialogue was possible in a situation of growing tensions because of the nuclear arms race. This meant not contributing to destabilizing pressures in the East, and at the same time avoiding being seen in direct alliance with militantly anti-communist forces in the West."

Late in the year a massive study of the churches and the cold war was published in Germany. While initial media reaction was somewhat muted - whether because of the book’s imposing size and abundant documentation, or because its appearance in German limited international interest in it, or because it came out just at the moment when media in Germany and elsewhere were riveted by the growing financial scandal around the Christian Democrats and former Chancellor Helmut Kohl, or because of a more general loss or lack of interest in the subject matter - it further fuelled the determination of the WCC to see a new look taken at its own history.

The churches in the world

The aftermath of the cold war in a far less abstract form occupied much of the attention of the international community in 1999. Besides creating enormous human suffering, the unfolding tragedy of Kosovo - the mass exodus of Kosovar Albanians under Serbian pressure, the NATO air campaign against Serbia, followed by the return of the refugees to often decimated towns and villages and the uneasy truce monitored by UN forces - put fears of instability and wider regional conflict which have troubled southeastern Europe since the break-up of the former Yugoslavia back on the front pages.

The WCC closely coordinated its response to the Kosovo crisis with three other international church organizations at the Ecumenical Centre - the Conference of European Churches (CEC), the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) and the World Alliance of Reformed Churches (WARC). All have member churches in the former Yugoslavia. International ecumenical relief aid to victims of the conflict was channelled through Action by Churches Together (ACT), with a notable role being played by the Orthodox Church of Albania.

CEC general secretary Keith Clements led a team of church leaders to Novi Sad and Belgrade in April; a second ecumenical delegation went to Albania and Macedonia at the end of May. Also in May, an ecumenically organized consultation in Budapest brought together some forty people from churches in Europe and North America. The participants, who included representatives of four churches in Yugoslavia - Lutheran, Methodist, Reformed and Serbian Orthodox - and from the Council of European [Catholic] Bishops Conferences - insisted that negotiations, in which the UN and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe should play a central role, were an urgent priority and "the only basis for a durable solution".

A joint statement by the four organizations welcomed the agreement ending the conflict endorsed by the UN Security Council on 10 June, noting that it marked a return to pursuing a solution within the framework of the UN Charter. The ecumenical statement insisted that a durable resolution of the conflict could only be built on the "solid foundation of respect for human rights", including the possibility for all who had been displaced or expelled to return to Kosovo and protection of ethnic Serbian communities in Kosovo from reprisals.

The WCC’s stance in the Kosovo crisis was not without its critics. During a panel discussion at the German Protestant Kirchentag in Stuttgart in June, Raiser and German defence minister Rudolf Scharping clashed over the NATO action. Scharping described the bombing campaign as an unavoidable last resort, arguing that Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic had disregarded 72 of 73 UN Security Council resolutions on the former Yugoslavia between 1991 and 1998 - the only exception being the one ending the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which was militarily guaranteed. Raiser contended that creating a peaceful Europe requires giving "absolute priority... to peaceful rather than military means of resolving conflicts". While NATO may have acted for humanitarian reasons, he said, its failure to respect the Geneva convention protecting civilians and civilian infrastructure turned the intervention into "a punishment against a whole people". The use of military force, he said, "must not become a legitimate instrument to protect human rights".

Concern for civilian victims was also central in the stance taken by the WCC and CEC on another European conflict later in the year. The general secretaries of the two bodies wrote to Russian Orthodox Patriarch Alexy II in November to express deep concern over the conflict in Chechnya. Acknowledging "the context of lawlessness and terrorism which has preceded the current armed intervention by the Russian armed forces", the letter deplored "the disproportionate and irresponsible use of force" being employed and appealed to political authorities in Russia and Chechnya "to manifest mercy to all people, especially the civilian population, the prisoners and the wounded". The letter also welcomed the patriarch’s earlier condemnation of attempts to deepen the conflict by manipulating religion.

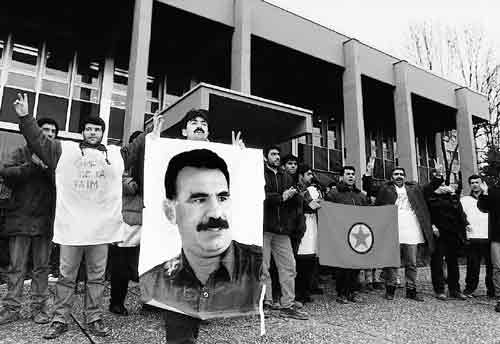

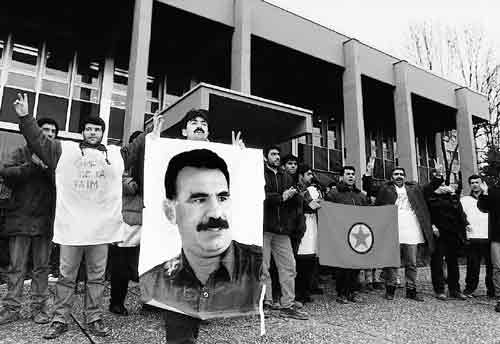

Members of the Kurdish community in Switzerland protesting at the Ecumenical Centre in Geneva

after Turkey’s arrest of Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan.

The arrest and detention by Turkey of Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan led to an unexpected visit of members of the Kurdish community in Switzerland to the Ecumenical Centre on 19 February. They presented an appeal regarding the situation to Raiser, and the WCC issued a statement calling on member churches in Europe to urge their governments "to seek a peaceful political solution to the plight of the Kurdish people" and asking the Turkish government to ensure Ocalan’s safety and to allow him a fair trial. In July, when Ocalan was sentenced to death, the WCC sent a letter to President Süleyman Demirel, noting the Council’s opposition to capital punishment as cruel and inhuman and appealing to him to grant clemency and commute the death sentence as a step towards breaking "the vicious cycle of violence in your country".

Throughout the year after holding an assembly in Africa, the WCC sought to express solidarity and fellowship with member churches affected by conflict situations on that continent.

A high-level delegation including the two general secretaries from the WCC and the All Africa Conference of Churches to the Democratic Republic of Congo in July met with President Laurent-Désiré Kabila and human rights minister Léonard She Otsitundu. Both the president and a number of Congolese church leaders told the ecumenical visitors that the chief responsibility for the continuing conflict in the east of their country lay with Rwanda and Uganda, which, having supported Kabila at the time of the overthrow of the Mobutu regime, now wished to maintain their hold on Congo’s resources. Indeed, said Kabila, his country’s natural wealth is a disadvantage; while the Congolese are prepared to share and live in peace with their neighbours, they cannot give up land or basic sovereignty in the interest of other countries. Konrad Raiser described Kabila’s call for a national debate on the future of the country, moderated by neutral parties and involving all political groups, as encouraging and said he hoped the churches would eventually contribute significantly to reshaping the country’s social and political institutions and constitutional framework.

During the visit some members of the ecumenical delegation spent a brief time in neighbouring Congo-Brazzaville, where a bloody civil war which has displaced hundreds of thousands of people since early 1999 has gone largely unremarked in the outside world except perhaps in France, the former colonial power. In one attack, militia forces killed six of nine members of a mediation team from the country’s Ecumenical Council of Churches.

| The WCC maintained its longstanding support of efforts to end the civil war which has decimated Sudan for most of its history since independence. In July the WCC and Caritas Internationalis convened a meeting of the Sudan Ecumenical Forum, created in 1994 to provide a shared platform for advocacy and coordinate churches’ efforts for peace with justice in Sudan. The Forum appealed to all parties in the conflict to break a year-long political stalemate in negotiations and to end the war in the context of the Intergovernmental Authority for Development. |

|

WCC visitors to the mausoleum of Simon Kimbangu, in Nkamba,

Democratic Republic of Congo. |

Two specific situations in Africa were the subject of "minutes" adopted by the Central Committee. The churches of Nigeria were commended for their witness for human rights, justice and peace in the changing situation there. The Committee offered them ecumenical support in their pursuit of reconciliation while urging them to persist in being a prophetic voice in the nation. Church leaders in Ethiopia and Eritrea were encouraged to continue exploring ways of peacefully ending the conflict which broke out between the two countries in May 1998 over a disputed border and has inflicted a "terrible, mounting toll of human life... on peoples who have suffered so terribly and for so long from war, repression and abject poverty".

Two WCC staff members were part of an ecumenical delegation that visited Sierra Leone in November to encourage the churches there in the context of a fragile peace agreement ending nine traumatic years of civil war which had made Sierra Leone, despite its wealth of resources, the world’s poorest country, according to the United Nations Development Programme. Half of the population are either displaced or war-affected, and more than one-third of these people have no access to humanitarian aid. During 1999 programmes for agricultural assistance, infrastructure rehabilitation, assistance to vulnerable sectors and training worth about US$2.2 million were implemented by the Council of Churches in Sierra Leone through the ACT network.

A particularly tragic element of the war in Sierra Leone has been the use of children as soldiers. During the Central Committee plenary session on Africa, Olara Otunnu, special representative of the UN Secretary General for Children and Armed Conflict, noted that the percentage of civilians - mostly women and children - among the casualties of war has risen from 5 percent in the first world war to 45 percent in the second world war to 90 percent in current conflicts. Today’s most pressing challenge, Otunnu said, is to translate "the impressive body of international instruments and local norms into commitments and actions that can make a tangible difference to the fate of children exposed to danger on the ground... We must reclaim our lost taboos; we must reaffirm the moral injunctions which have been eroded from our societies." To this effort he urged that the WCC lend its "moral influence and authority".

In Indonesia, communal violence, attacks on Christian and Muslim places of worship and human rights violations by the security forces continued to be a concern throughout 1999. The WCC maintained close contact with the churches and ecumenical bodies there, particularly those in East Timor and Irian Jaya. A nine-member ecumenical delegation to Indonesia, organized in January by the WCC and the Christian Conference of Asia, met with then-President B.J. Habibie. There was also a staff visit to East Timor in late June and early July. In September the Central Committee called attention especially to the dangers confronting East Timor in the post-referendum period, to communal violence in Ambon and to repressive measures by the security forces in Aceh and Irian Jaya. It urged member churches elsewhere to pray for the churches and people of Indonesia and to support and encourage the Indonesian churches’ work for peace, justice and reconciliation.

The WCC joined the LWF, the Latin American Council of Churches and the US National Council of Churches in sponsoring an "Ecumenical Forum of Cooperation for Colombia" in Bogota in June. Representatives of Protestant and Roman Catholic churches met with international non-governmental organizations to discuss how to meet the pressing needs of a country torn by multi-faceted violence - involving the army, guerrilla groups, para-military groups and drug cartels - which has driven more than 1.5 million Colombians from their homes.

Looking back on the proliferation of conflicts in almost every part of the world, the Central Committee adopted a substantial "memorandum and recommendations on response to armed conflict and international law". While acknowledging the inseparability of peace and justice, the memorandum says that conflicts of the past decade require renewed consideration of "how the complementary and inter-related needs of people for both peace and justice can be more effectively related". Reaffirming the WCC’s conviction that the UN is "the unique instrument of the peoples of the world for guaranteeing respect for the international rule of law", the recommendation urges that the WCC facilitate a study of the ethics of humanitarian intervention, "taking into account the legitimate right of states to be free of undue interference in their internal affairs and the moral obligation of the international community to respond when states are unwilling or incapable of guaranteeing respect for human rights and peace within their own borders".

Elsewhere in the oikoumene

Perhaps the most widely noted ecumenical event of 1999 took place on 31 October in St Anna’s Lutheran Church in Augsburg, Germany, where Cardinal Edward Cassidy, president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, and German Lutheran Bishop Christian Krause, president of the Lutheran World Federation, signed a Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification. In a statement made in Rome, Pope John Paul II described this agreement about one of the most contentious issues of the Protestant Reformation as "a milestone on the not-always-easy road towards the restoration of full unity in Christ". Indeed, the road towards the Joint Declaration itself was none too easy: a large group of prominent German Protestant theologians had criticized it, and ambiguous signals from within the Vatican after the LWF adopted the text in 1998 had cast a shadow, at least temporarily, over the prospects of future dialogue between the two churches.

Bishop Krause and Cardinal Cassidy signing the Lutheran-Catholic

Joint Declaration on Justification in Augsburg.

In May the official commission for theological dialogue between Anglicans and Roman Catholics released an agreed text on "The Gift of Authority". It offers an extensive theological analysis of the nature and exercise of authority in the church; and the commission suggested that if this analysis were to be accepted, authority would no longer constitute a church-dividing issue between Anglicans and Roman Catholics. But despite the hopes of the commission that readers would carefully study the statement itself before commenting on its recommendations, most early reports of the document seemed mainly interested in its suggestion that Anglicans might accept the primacy of a pope whose specific ministry concerning the "discernment of truth" is "a gift to be received by all the churches" and whose universal primacy will "help to uphold the legitimate diversity of traditions".

While church union negotiations are considered in some ecumenical quarters to represent a bygone model for working towards the unity of the church, 1999 saw some progress on a number of longstanding efforts in this area, as well as at least one new initiative.

In January, representatives of the nine US denominations involved in the Consultation on Church Union - whose origins can be traced to a sermon by former WCC general secretary Eugene Carson Blake in 1960 - met in plenary for the first time in ten years. They recommended that the participating churches "enter into a new relationship to be called Churches Uniting in Christ" to be inaugurated publicly during the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity in 2002, aiming at full reconciliation of their ministries (a long-standing difficulty in view of divergent views about the office of bishop) by 2007.

Union efforts that have waxed and waned among Presbyterians in South Africa since 1958 finally culminated in the formation of the Uniting Presbyterian Church of Southern Africa in September.

For more than two decades, three Indian churches - the Church of North India, Church of South India and the Mar Thoma Church - have been involved in protracted if not dormant discussions of church unity. But a decision taken in July that the highest executive bodies of the three churches should meet together to identify decisive and visible steps forward in common worship, witness and mission had the effect of infusing new life into their joint council. At that meeting, which took place in November, it was agreed to use a common lectionary beginning in Advent 2000 and to prepare a common eucharistic liturgy for all three churches. A message to the churches reaffirmed "that we belong to the one church of Jesus Christ in India", announced the appointment of the first full-time secretary for the joint council, and spoke of common concerns about Christian witness in the midst of growing communal disharmony in India and "increasing threats to the secular foundations of the country". Relations among religious groups and especially the status of religious minorities continued to be subjects of profound concern in India throughout the year, eliciting a number of reactions from churches and ecumenical bodies there.

In November, the United Church of Christ in the Philippines and the Philippine Independent Church initiated a covenant of partnership which could lead to full union "in God’s own time".

In the USA, the National Council of Churches marked its 50th anniversary in Cleveland in November in a climate of transition (general secretary Joan Brown Campbell retired at the end of 1999, and United Methodist clergyman Robert Edgar, a former US congressman, was named to replace her), financial difficulties (a projected US$4 million deficit on the 1999 budget), allegations of poor management (which had led the United Methodist Church temporarily to withhold its contribution to the NCC) and a restructuring that would probably reduce by a third the size of its New York staff.

As attention continued to focus on the dawning of a new millennium (with some continuing and unresolved disagreements about whether this would be in 2000 or 2001), Italian Lutherans announced in January that they would not take part in events to be held in Rome by the Roman Catholic Church to mark the "Jubilee Year" 2000. The Lutheran statement said a jubilee should be an "act of penitence" giving praise "to God alone" and avoiding "all false glory of the church", adding that the correct place to commemorate the 2000th anniversary of the birth of Christ is the Holy Land, not Rome. Italian Protestants were also among the sharpest critics of the Vatican’s publication in September, in time for the Jubilee Year, of a new edition of the "Manual of Indulgences".

The May visit of John Paul II to Romania was the first by a pope to a predominantly Orthodox country in 1000 years. On the final day of the visit, the Pope and Romanian Orthodox Patriarch Teoctist attended two major outdoor religious services in Bucharest, a three-hour Orthodox liturgy in the morning and an afternoon Catholic mass in a park where more than 200,000 people, including many Romanians from largely Catholic areas in northern Transylvania, were present.

In January, officials of four religious groups in Russia - Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Buddhism - announced plans to form a permanent consultative body, the Interfaith Council of Russia, to foster dialogue and cooperation, discuss current social problems and witness to shared values "to the authorities and the people". In late November high-level representatives of 33 traditional Christian communities from the former Soviet Union, meeting in Moscow, called for closer cooperation among Christians. Patriarch Alexy II of the Russian Orthodox Church gave the opening speech at the conference, and Cardinal Edward Cassidy read a message of encouragement from Pope John Paul II. Observers said the spirit of the conference was in sharp contrast to the often-tense interchurch atmosphere in Russia.

In New York in September, Archbishop Demetrios was enthroned as primate of the 1.5-million member Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, ending a three-year period of tensions - and in some quarters open talk of a split in the church -which had marked the tenure of his predecessor, Archbishop Spyridon, who resigned his position in August.

In December, Karekin II was enthroned as primate of the Armenian Apostolic Church (Etchmiadzin), taking the name of his predecessor who had died earlier in the year. The church, one of the world’s most ancient, will celebrate the 1700th anniversary of Armenia’s declaration of itself as a Christian state in 2001.

Also in December a ten-day Parliament of World Religions brought about 6000 people to Cape Town, South Africa. Much of the meeting was devoted to preparations for a United Nations-organized "spiritual summit" of world religious leaders in August 2000, just before the UN Millennium Heads of State summit.

Obituaries

Among the prominent ecumenical pioneers and leaders who passed away in 1999 was New Testament theologian and ecumenist Oscar Cullmann, who died on 16 January at the age of 96. A Lutheran from Strasbourg who spent most of his career teaching at the Reformed theological faculty in Basel, an observer at the Second Vatican Council who had the ear of three popes, Cullmann tirelessly put his New Testament scholarship at the service of Christian unity.

Two Africans prominent for many years in the work of the WCC died in 1999. J. Henry Okullu, a Kenyan Anglican bishop, died on 13 February at 70. An outspoken and courageous voice for peace and justice in his own country, where he served three terms as chair of the national council of churches, Okullu’s international ecumenical service included 23 years (1975-98) as a member of the WCC’s Central and Executive Committees. Aaron Tolen died on 7 April in Yaoundé, Cameroon. From 1976 to 1983 he was moderator of the WCC’s Commission on the Churches’ Participation in Development, and from 1983 to 1991 he was a member of the WCC’s Central Committee. He was elected one of the WCC’s presidents by the Canberra assembly in 1991.

Anwar Barkat, who died in Pakistan on 14 April, was associate director of the Ecumenical Institute in Bossey from 1968 to 1970 and a member of the WCC Central and Executive Committees from 1975 to 1980. In 1981 he rejoined the WCC staff as director of the Programme to Combat Racism until 1985; later he served in the WCC’s liaison office at the United Nations in New York.

Following a long illness, Karekin I, Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians, died in Etchmiadzin on 29 June at 66. An ecumenical pioneer in the Middle East, he was elected to the WCC Central and Executive Committees in 1968 and from 1975 to 1983 he served as vice-moderator. In 1995 he was called from his position as primate of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Cilicia to Etchmiadzin to guide the renewal of the church in Armenia after decades under a hostile political system.

Jaime Wright, general secretary of the United Presbyterian Church of Brazil from 1977 to 1983, died on 29 May. An ecumenical leader and human rights advocate during the 21 years of military dictatorship in his country, Wright was best known for his involvement in the 1985 publication of a massive documentary account of human rights abuses during that period under the title Brazil: Never Again.

Sun Ai Lee-Park, who died in Korea on 21 May at 68, was a well-known Asian feminist theologian who founded and edited the ecumenical magazine In God’s Image. She was the programme coordinator of the Asian Women’s Resource Centre, based in Hong Kong and later in Seoul, from the late 1980s until the early 1990s.

Cardinal Basil Hume, who led the Catholic Church in Britain and Wales for 24 years, died of cancer on 17 June. He was 76. As a Benedictine abbot in North Yorkshire he had pioneered Catholic participation in a local council of churches; many years later he reversed his church’s long history of isolation by leading it into the Council of Churches for Britain and Ireland.

Dom Helder Camara, branded by his critics as the "Red Bishop" because of his unswerving commitment to social justice as archbishop of Olinda and Recife in Brazil, died on 27 August at the age of 90.

Johannes Hanselmann, German Lutheran bishop of Bavaria until his retirement in 1994, and president of the Lutheran World Federation from 1987 to 1990, died on 2 October at the age of 72, less than a month before the signing of the Lutheran-Roman Catholic Joint Declaration in whose drafting he had played a key role.

Former WCC staff member Guillermo Cook died in October after a long period of ill health. Active for many years in building bridges between evangelicals and mainline Protestants in Latin America, and a keen student of the theology and spirituality of indigenous peoples in Central America, Cook served as consultant to the WCC for the organization of the 1996 world mission conference in Salvador, Brazil.

Marlin VanElderen

Marlin VanElderen is WCC Publications editor.

Back to main "Who are we?" page

© 2000 world council of churches | remarks to webeditor