Interview with Nobel Peace Laureate José Ramos-Horta

|

Interview with Nobel Peace Laureate José Ramos-Horta |

| So often we witness, on our television screens, the violence of a country being torn apart by civil war, or a people struggling to eject foreign invaders from their soil. The people of East Timor have been struggling for years - for them it became an armed struggle - against the force of the Indonesian army of occupation. Television cameras brought us the horror of the final acts of cruelty and oppression by the Indonesian armies. Thousands of East Timorese had to flee and, despite the peace agreements that followed, have still not been able to return home. In this issue of ECHOES, with its focus on naming some of the violences which trouble our world, we wanted to speak with someone from a country which has been brutalised and which has begun on the long path to full recé Ramos-Horta agreed to share his reflections. For well over a decade he has traveled the world, an East Timorese in exile, earning enormous respect from governments and NGOs alike as he patiently and persistently worked for the independence of East Timor.* |

ECHOES: How would you describe the violence done to your people? José Ramos-Horta: The violence unleashed on the people of East Timor was of such a scale that one can easily compare it with the greatest crimes against humanity that took place in this century, namely the genocide against the Armenians, the Jewish Holocaust or the Khmer Rouge holocaust. Out of a population of 700,000 in 1975, at least 200,000 were dead by 1979, only three years after the invasion by Indonesia. Then, in September 1999 the whole world was witness to one of the most graphic and televised systematic destruction of a country. E: What has been the long-term effect ? JRH: The long-term effect is a traumatised society, two generations growing up in violence, which make it extremely difficult for the whole process of national healing and reconciliation. But the people of East Timor are a unique people, incredibly resilient, forgiving, tolerant. With a leadership that preaches tolerance, reconciliation, non-violence, we will be able to consolidate peace. E: What are the practical steps you can take? JRH: One practical step is to talk about the need for reconciliation and forgiveness. Yes, just talk as often as you can. How does one solve problems in a family context? You talk things over. Obviously, there are other steps to be taken, such as the guilty party asking for forgiveness and offering some form of reparation to the victims, doing community work, repairing the damaged properties or cleaning up the streets. I am the head of our National Reconciliation Commission; working with the churches we conti-nue what we know is a long process of dialogue, healing and forgiving. In the case of more serious war crimes, then there has to be a special tribunal to judge these crimes. Justice cannot be revenge or reprisal. In our case, I have said quite emphatically that the National Council of Maubere Resistance (CNRT) should not be involved in the judicial system. We are a political movement and political movements are never impartial judges. So, the judicial system in East Timor right now is in the hands of the United Nationsí Administration until such a time as our courts and judges are fully established. I have had two meetings with our newly appointed judges and paid tribute to them, offered my deep, sincere respect and support. E: At this point in the history of your people, can you say the violence, the incredible loss of lives, was worth it? JRH: I would not put it this way. Instead I would say we must build a country, construct a new society, free from violence, hatred and poverty. We must eliminate poverty, malaria, TB; we must provide each child with books, computers and milk; we must spend more on buying computers for the children than in weapons. If a few years from now, looking around us, we see a peaceful, tolerant and prosperous society, then I would say we did not betray the sacrifice of so many. No ideology, religion or cause may justify or prevail over the sanctity of life. However, if one has to die for freedom and dignity, then those who survive must not betray the death of those who gave their life for their country and for freedom. |

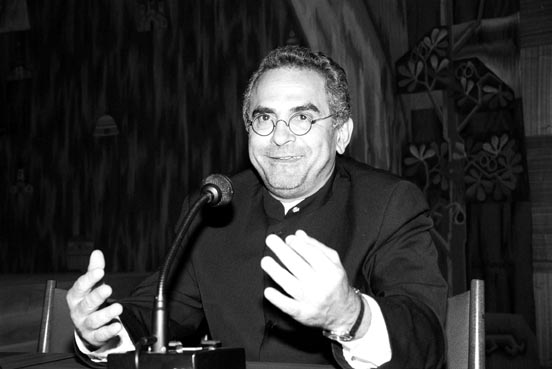

José Ramos-Horta speaks to WCC staff in Geneva, 12 April 2000. Photo: Catherine Alt, WCC |

It is an overwhelming task ahead of us; to rebuild the country from the ashes of destruction, house after house, school after school, clinic after clinic, entire towns, market places. We must provide jobs to the unemployed, offer a support system to the widows and orphans. We must reduce illness and poverty to human levels. At the same time, we must build a truly democratic society, a system of government with checks and balances. Our women must regain a place in the policy and decision-making institutions from where they were always alienated. We must prevent corruption from becoming rooted in our society and system of government. The media, NGOs and civil society in general must play an active role in this whole enterprise of nation-building. E: In the light of what you have said, could you des-cribe the nature and character of the state you are planing? What kind of constitution do you foresee? Being a predominantly Catholic country, will Catholicism be the official religion? JRH: We have some firm ideas as to the future constitution of the country. We have already a Magna Carta, adopted by acclamation at the founding of the CNRT, which enshrines all the human rights values and principles: rule of law, freedom of expression and assembly, freedom of religion. We have committed ourselves to accede to and ratify all major international human rights instruments that would make East Timor a country totally open to international scrutiny. As far as religion is concerned there will be no official state religion and there will be no special privileges for a particular church. However I believe that, because of the role of the Catholic Church in the fields of education, health and cultural preservation, I would support offering it some financial assistance. They deserve it. The same goes for our small Protestant Church. They have done a lot for the country as a whole. We have an even smaller Muslim community of a few hundred people. Some are East Timorese, others are East Timorese of Arabic ancestry, and others are Indonesians. They too have rights, must be supported, cherished. It is our diversity that makes us richer. |

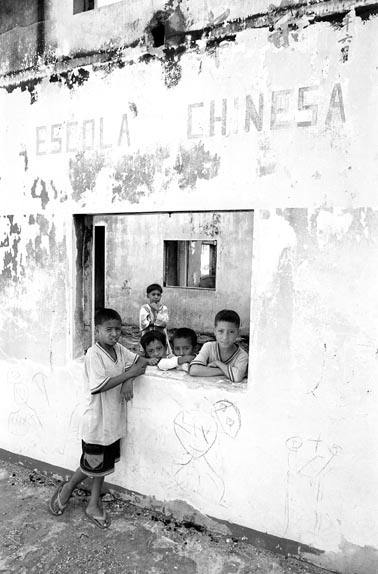

Photo: Peter Williams, WCC |

E: In this age of globalisation, what is the future of a small country like East Timor, which does not yet have a significant market to offer? Can East Timor have a future other than as an appendage of another larger economy, such as Indonesia or Australia? Will East Timor have escaped one form of violence only to be confronted by another form - we might call it economic violence? JRH: Globalisation has been a one-way street used by the richer countries. The poorer countries have been largely victims. However, one cannot run away from it. It is there to stay. We must make the best of it because there are many positive elements, such as access to information. We must educate our people, provide them with the tools of knowledge so that our societies can survive and compete. Singapore did not start off rich. Singapore is in the global economy and has been doing very well. We do not aspire to be another Singapore. But we have great potential to prosper. We have a country blessed with a resilient and hardworking people and abundant natural resources - plenty of fertile land and rain, the best coffee in the world, an ocean that is rich in fish, and a host of mineral riches such as oil, gas and marble. I donít think that having Australia as our richest and closest neighbour is a curse. Quite the opposite, poor countries can develop better when they are on a major trading route, near major world economic and financial centres, near to a rich country. Our only, and real, concern is the tragic violence engulfing many parts of Indonesia that is tearing apart that great nation. E: Are you happy with the progress you have made so far ? You are still very much in the hands of the United Nations? Is that a mixed blessing? JRH: The UN is the favourite whipping boy and scapegoat for the failures of member states. The Security Council prints truckloads of resolutions imposing more and more responsibilities on the UN Secretariat and the secretary general to resolve a host of problems around the world. It would be great if the Security Council would also print out equal amount of monies to pay for all this. Having said this, I would add also that there are a lot of incompetent people serving with the United Nations. But who is to blame? When the Secretariat prepares a mission, it sends governments a list of the personnel it needs. Some governments send their very best; some send a nephew or son of an influential leader, and some try to get rid of a political enemy by sending him out of the country and dumping him on the UN. In the case of East Timor, we have some very committed and competent people, like Sergio Vieira De Mello, who work an average of 15 hours a day, seven days a week. We also have had some really incompetent and lazy people from all cultures and nationalities. In other words, the UN is no different from so many other large governments. On balance, the UN performance in East Timor has been positive. At least it has brought a sense of peace and security to the people, the greatest gift you can give a people after 24 dark years of fear and terror. As for nation-building, institution-building, national construction and development, things are progressing better now after several months of a frustratingly slow start. * Note: This interview was conducted some weeks before Mr Ramos-Horta was sworn in as a member of the East Timor Transitional Cabinet, with responsibility for foreign affairs. He also assumed responsibility for foreign relations of the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET). ECHOES warmly congratulates Ramos-Horta on his return to his homeland and wishes him well for the challenges that lie ahead. |